Printed with permission from eMedicine.com

Updated: Feb 11, 2009

Introduction

BACKGROUND

The presentation of degenerative disease in focal areas of the cerebral cortex is the hallmark of the family of diseases called frontotemporal dementia. Cases of elderly patients with progressive language deterioration have been described since Arnold Pick's landmark case report of 1892. His case study, "On the relationship between aphasia and senile atrophy of the brain", still serves as a frame of reference for apparently focal brain syndromes in diffuse or generalized degenerative diseases of the brain.[1 ]As Pick stated, “simple progressive brain atrophy can lead to symptoms of local disturbance through local accentuation of the diffuse process.”

In 1982, Mesulam reported 6 patients with progressive aphasia, gradually worsening over a number of years, who did not develop a more generalized dementia.[2 ]Since Mesulam's publication, numerous other cases have been reported. This disorder, which is currently termed primary progressive aphasia (PPA), has gained acceptance as a syndrome. Subsequently, the primary progressive aphasia syndrome was defined as a disorder limited to progressive aphasia, without general cognitive impairment or dementia, over a 2-year period. Many patients do develop more generalized dementia later in the course of the illness, as those reported by Kirshner et al.[3 ]Less commonly, cases of isolated right frontal or temporal degeneration have been reported. These patients experience failure to recognize family members (prosopagnosia), failure to remember topographic relationships, and similar disorders.

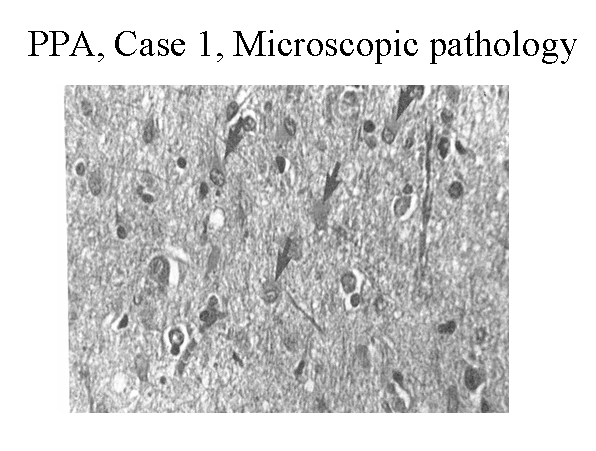

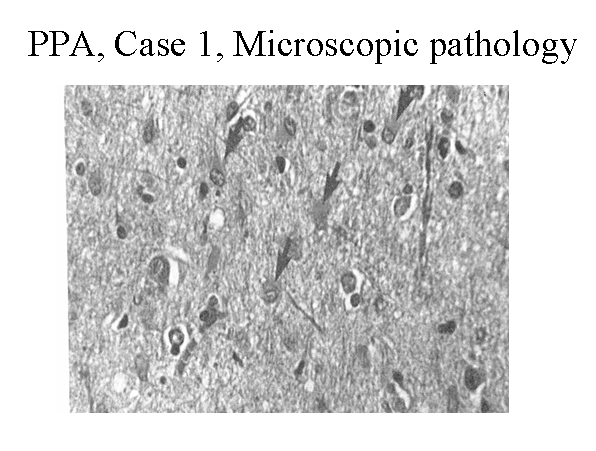

Hematoxylin and eosin stain of the left frontal cortex from a patient with primary progressive aphasia. This shows loss of neurons, plump astrocytes (arrow), and microvacuolation of the superficial cortical layers. Reproduced with permission of John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Hematoxylin and eosin stain of the left frontal cortex from a patient with primary progressive aphasia. This shows loss of neurons, plump astrocytes (arrow), and microvacuolation of the superficial cortical layers. Reproduced with permission of John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

In England, cases of frontal lobe dementia were described with progressive dysfunction of the frontal lobes. In a series of case reports, Neary and Snowden outlined a syndrome with initial symptoms that were suggestive of psychiatric illness. However, the following frontal lobe behavioral abnormalities appeared over time: disinhibition, impulsivity, impersistence, inertia, loss of social awareness, neglect of personal hygiene, mental rigidity, stereotyped behavior, and utilization behavior (ie, tendency to pick up and manipulate any object in the environment). These descriptions included language abnormalities such as reduced speech output, mutism, echolalia, and perseveration.

In recent years,

the condition described in the North American literature as primary progressive

aphasia and that has been described in the European literature as frontal

dementia have been combined under the term frontotemporal dementia

(FTD). This lumping refers to the frontal lobe syndrome described by

Neary and Snowdon[4 ]as interchangeably behavioral variant frontotemporal

dementia (bvFTD) or frontal variant frontotemporal dementia (fvFTD) and divides

progressive aphasias into 2 groups — progressive nonfluent aphasia (PNFA)

and semantic dementia (SD).

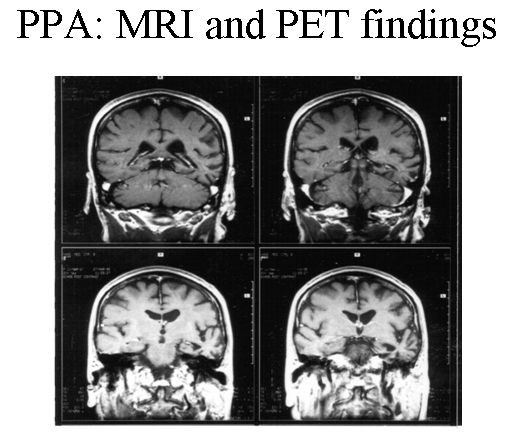

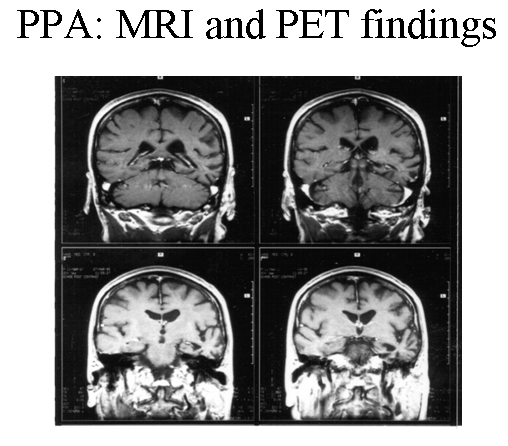

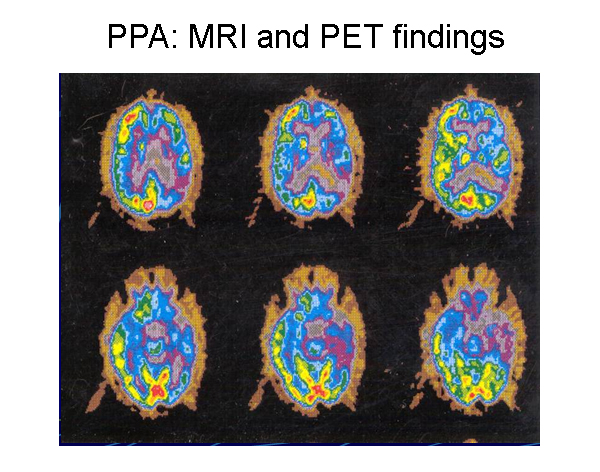

Patient with progressive nonfluent aphasia. MRI showing focal, left temporal atrophy. Reprinted from Neurology in Clinical Practice, 4th ed. Kirshner H. Language and Speech Disorders. Copyright 2004, with permission from Elsevier.

Patient with progressive nonfluent aphasia. MRI showing focal, left temporal atrophy. Reprinted from Neurology in Clinical Practice, 4th ed. Kirshner H. Language and Speech Disorders. Copyright 2004, with permission from Elsevier.

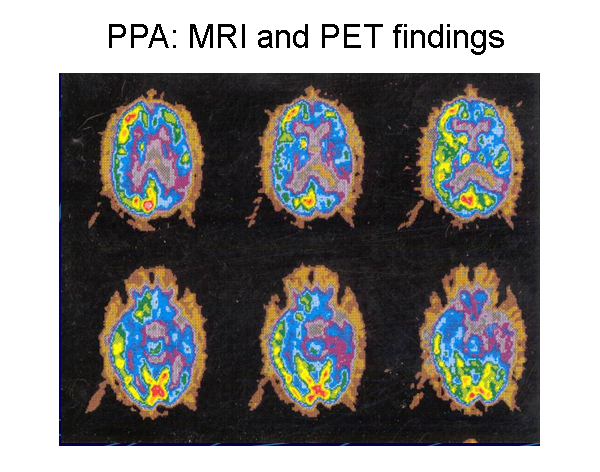

Patient with progressive nonfluent aphasia. Positron emission tomography (PET) scan indicating hypometabolism of glucose in the left hemisphere. Reprinted from Neurology in Clinical Practice, 4th ed. Kirshner H. Language and Speech Disorders. Copyright 2004, with permission from Elsevier.

Patient with progressive nonfluent aphasia. Positron emission tomography (PET) scan indicating hypometabolism of glucose in the left hemisphere. Reprinted from Neurology in Clinical Practice, 4th ed. Kirshner H. Language and Speech Disorders. Copyright 2004, with permission from Elsevier.

A 2008 review by Josephs et al used frontotemporal dementia as an umbrella term referring clinical syndromes of frontal dementia or progressive aphasia, and the term frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) to relate to pathologies associated with the frontotemporal dementia syndromes.[5 ] We shall maintain this distinction with frontotemporal dementia referring to syndromes and frontotemporal lobar degeneration referring to pathologies.

Considerable progress has been made with regard to the genetics

and molecular pathology of these disorders. Many patients with frontotemporal

lobe dementia syndromes have tau pathology, and mutations in the tau gene

have been found in many of these patients. More than 50% of cases

lack tau pathology but have ubiquitin immunoreactive inclusions in the cytoplasm

or nucleus or ubiquitin immunoreactive neurites. This group has

been designated frontotemporal lobar degeneration-ubiquitin (FTLD-U). The

TAR-DNA binding protein (TDP-43) is a major component of most of these ubiquitin-positive

cases. Progranulin mutations have been found in some of the nontau, ubiquitin,

and TDP-43 positive hereditary frontotemporal lobe dementia cases. Mutations

in at least 4 other genes have also been associated with ubiquitin-positive

familial frontotemporal lobe dementia syndromes. Finally, the smallest

group of frontotemporal lobe dementia cases have neither tau norubiquitin/TDP-43pathology.

With better understanding of frontotemporal lobar degeneration, the tau pathology

associated with some progressive nonfluent aphasia and behavioral variant

frontotemporal lobe dementia cases was also found in progressive supranuclear

palsy (PSP) and corticobasal degeneration (CBD), and the ubiquitin-immunoreactive

inclusions found in the frontal cortex in some behavioral variant frontotemporal

lobe dementia are found in upper and lower motor neurons in amyotrophic lateral

sclerosis (ALS). Moreover, about 10% of patients with amyotrophic lateral

sclerosis have significant dysfunction in behavior and executive function,

and some patients with frontotemporal lobe dementia develop motor neuron disease

as their illness progresses.

FREQUENCY

United States

The exact prevalence of frontotemporal lobe dementia is unknown. Among patients presenting with dementia who are younger than 65 years, the prevalence may be similar or greater than that of Alzheimer disease.[6 ]Some series based on brain pathology have estimated that frontotemporal lobe dementia comprises as many as 10% of cases of dementia. In the United States, estimates are generally lower.

International

Studies from Lund, Sweden and Manchester, England estimate that frontotemporal lobe dementia accounts for approximately 8% of patients with dementia. Probably the most accurate information comes from a Dutch study by Stevens et al, who reported 74 cases in a population of 15 million (ie, 5 cases per million). Among those aged 60-70 years, the prevalence was 28 cases per 100,000.[7 ]

MORTALITY / MORBIDITY

Frontotemporal lobe dementia, like all dementing illnesses, shortens

life expectancy. The exact influence on mortality is unknown. The rate of

progression is variable. Patients with associated motor neuron disease tend

to have much shorter life expectancy.

- Among patients younger than 65 years, frontotemporal lobe dementia and Alzheimer disease have similar prevalence. Among patients in their 70s and older, the prevalence of Alzheimer disease far exceeds that of frontotemporal lobe dementia. As a result, the average age of onset for frontotemporal lobe dementia is younger that that of Alzheimer disease.

- The rate of progression from focal presentation to a more generalized dementia varies. Some patients experience only aphasia for periods exceeding 10 years, while others progress to dementia within a few years.

- In a subset of cases, motor neuron disease develops. This subgroup has a higher mortality rate from frontotemporal lobe dementia than other affected patients. Swallowing difficulty and aspiration pneumonia are especially common in this subgroup of patients, but even patients with primary progressive aphasia can develop dysphagia late in the course of the illness.

SEX

Frontotemporal dementia can develop at almost any age in either gender. The most complete review, compiled by Westbury and Bub, investigated 112 published cases prior to 1997; the series included 66% males and 34% females.[8 ]

AGE

Most patients with frontotemporal dementia present in their 50s or 60s. In the 1997 review by Westbury and Bub, the mean age of onset was 59 years. The modal age was 64 years.[8 ]

Clinical

HISTORY

- For the subgroup

of frontotemporal dementia with primary progressive aphasia, the presenting

symptoms involve a deterioration of language function. At first, other aspects

of cognitive function and behavior may seem entirely normal. Pick first

described the presentation of focal language deterioration as a sign of

a dementing illness. Sporadic cases were presented into the 20th century

until Mesulam named the syndrome of primary progressive aphasia.[2

]Other authors such as Kirshner et al[3 ]described focal,

aphasic presentations in patients who later showed signs of more general

dementia. Patients with primary progressive aphasia who do not depend on

their verbal skills for their livelihoods may continue to function at work.

Artistic expressions may even increase or be taken on as new hobbies in

these patients, although, according to Miller and Hou[9

], their productions are often compulsive in style.

- The most

common presenting symptom is word-finding difficulty. However, decreased

fluency or hesitancy in producing speech, difficulty with language comprehension,

and motor speech difficulties (eg, dysarthria) are also common. The

descriptions of language syndromes in primary progressive aphasia have

become more complex.

Initially, primary progressive aphasia was divided into 2 subtypes:

(1) a progressive nonfluent aphasia, and

(2) fluent aphasia with anomia.

More recently, 3 subtypes have been described:

(1) progressive nonfluent aphasia, which includes dysarthria and a Broca-like aphasia, with hesitant groping speech and difficulty producing phonemes,

(2) semantic dementia, a fluent aphasia with impaired naming and impaired knowledge of word meanings, and

(3) the logopenic, or logopenic/phonological variant, of primary progressive aphasia, in which patients have impaired word-finding with hesitant speech and impaired repetition.[10 ]These subtypes, while somewhat arbitrary and probably overlapping to some degree, are associated with different localizations of cortical atrophy and with differences in biological markers, as will be discussed later.

- The mode

of presentation suggests a focal lesion of the left hemisphere language

cortex, but a focal lesion, other than evidence of focal atrophy, is

usually not found. MRI, especially when combined with voxel-based

morphometry, has become much more accurate in mapping localized areas

of cortical atrophy.

- The course

is progressive, with slowly worsening language function.

- The most

common presenting symptom is word-finding difficulty. However, decreased

fluency or hesitancy in producing speech, difficulty with language comprehension,

and motor speech difficulties (eg, dysarthria) are also common. The

descriptions of language syndromes in primary progressive aphasia have

become more complex.

- Patients with

progressive, nonfluent aphasia usually have non-Alzheimer pathology, most

commonly a tau-based disorder.

- Fluent aphasia

at onset is a less specific finding than nonfluent aphasia. Some patients

with progressive fluent aphasia have Alzheimer disease and others fit

the rubric of frontotemporal dementia, usually a nontau variety (see below).

- Semantic dementia,

a disorder described by Hodges and colleagues in the United Kingdom, is

characterized by a progressive loss of naming ability and a loss of the

ability to understand the meaning of words.[11 ]The

aphasia is usually fluent, without dysarthria, though there may be word-finding

pauses. Most patients with semantic dementia and frontotemporal dementia

have a nontau pathology, characterized by ubiquitin staining, and some have

the progranulin mutation (see below). Other patients with semantic dementia

have had Alzheimer disease.

- The logopenic/phonological

variant is usually a manifestation of Alzheimer disease.

- One area of

controversy in primary progressive aphasia concerns whether a generalized

dementia eventually develops in all patients with primary progressive aphasia.

- The literature contains many cases of slowly progressive language dysfunction, developing over a period as long as 10-12 years, without obvious deterioration of other cognitive functions that would justify a diagnosis of dementia.

- The incidence

of dementia in patients with primary progressive aphasia is unknown

but likely approaches 50% over several years.

- In frontal

lobe dementia studies, presenting symptoms often involve alterations in

personality and social conduct.

- Patients with the frontal variant of frontotemporal dementia may become disinhibited, developing a "witzelsucht," or fatuous sense of humor. Conversely, they may become apathetic, with little spontaneous speech or activity.

- They tend to neglect personal hygiene and to lose sensitivity to the effects of their behaviors on others.

- Some develop frank frontal lobe behavioral abnormalities such as hyperorality, utilization behavior (ie, picking up and manipulating any object in the environment, appropriate or not), and inappropriate sexuality.

- In these

descriptions, language function either is described as reduced in output

(leading to muteness) or is characterized by perseveration, stereotyped

responses, or even echolalia.

- A subgroup

of patients with frontotemporal dementia develops signs and symptoms of

motor neuron disease, such as fasciculations, muscle wasting and weakness,

and bulbar symptoms. These patients have ubiquitin pathology. At least 2

genetic defects have been reported in patients with frontotemporal dementia

and motor neuron disease.

- Another subgroup of patients with frontotemporal dementia experiences progressive right hemisphere dysfunction. Why reports of progressive right hemisphere degeneration have been so much less common than those of progressive aphasia is unclear. Finally, a genetic disease with combined inclusion body myopathy and frontotemporal dementia has been described.

Diagnostic considerations

- Frontotemporal dementia is somewhat intermediate between focal disorders of the brain and more generalized neurodegenerative diseases.

- The most important differential diagnoses for frontotemporal dementia involve focal pathologies such as brain tumors, abscesses, and strokes, as well as differentiation from the more common dementing illness, Alzheimer disease.

- In distinguishing between frontotemporal dementia and other focal lesions, gradually progressive onset, usually over years, is the key feature.

- Brain imaging studies are helpful in ruling out focal, destructive, or neoplastic lesions. Whitwell and colleagues used voxel-based morphometry on MRI to distinguish differing patterns of lobar atrophy in variants of frontotemporal dementia with and without motor neuron disease.[12 ]PET studies have also been helpful in the diagnosis of frontotemporal dementia.

- In distinguishing frontotemporal dementia from Alzheimer disease, the involvement of specific cognitive functions is the most important differentiating factor.

- Grossman compared

4 patients with primary progressive aphasia to 25 patients with presumed

Alzheimer disease.[13 ]

- Patients with primary progressive aphasia had preserved memory and visuospatial functions, while those with Alzheimer disease had nearly universal involvement of these functions.

- Patients with primary progressive aphasia performed worse than patients with Alzheimer disease on syntactic and speech fluency tasks and had more severe impairment of attention (eg, digit span).

- In general, these differences between frontotemporal dementia or its primary progressive aphasia variant and Alzheimer disease reflect the pathologic involvement of the frontal and temporal lobes, particularly in the left hemisphere, as compared to the early involvement in Alzheimer disease of the hippocampi and parietal lobes.

Physical

Physical and neurologic examinations reflect mainly

the mental status abnormalities described under History.

- Many patients have a nonfluent speech pattern, and virtually all have some degree of difficulty in naming or word finding.

- Behavioral alterations and frontal lobe symptoms have been previously outlined.

- Ideation tends to be concrete with poor abstraction and organization of responses and delayed shifting of cognitive sets.

- Visual and spatial functions and constructional tasks are much less affected, except as influenced by behavioral and organizational difficulties.

- Motor skills usually are spared, except for perseverative or inattentive responses and difficulty with temporal sequencing of tasks.

- Specific ideomotor apraxia is rare.

- Memory usually is preserved for orientation, although information retrieval may be difficult.

- Frontal release signs such as a positive glabellar sign, snout, grasp, and palmomental responses may develop.

- In a minority of patients, extrapyramidal signs, such as rigidity or even a full-blown parkinsonian syndrome of rigidity, akinesia, and tremor, may develop. An overlap also exists with the syndrome of corticobasal degeneration, in which rigidity and apraxia of the upper limbs may coexist with neurobehavioral symptoms much like those associated with the syndrome of primary progressive aphasia.

- Widespread muscle atrophy, weakness, fasciculations, bulbar signs, and hyperreflexia may ensue in patients with motor neuron disease. Muscle weakness is also seen in the rare variant with inclusion body myopathy.

- As mentioned earlier, some patients may show artistic or musical talents, sometimes with greater expression than before the onset of the illness.

CAUSES

The cause of frontotemporal lobe dementia is unknown, but significant

evidence supports a genetic component to these syndromes.

- As many as 40-50% of patients with frontotemporal lobe dementia have an affected family member.

- In the Dutch study, 38% of the index cases of frontotemporal lobe dementia had a first-degree relative with similar symptoms at an early age of onset.

- The 2008 review by Seelaar and colleagues found that 27% of cases had autosomal dominant inheritance (see below).[14 ]

- The molecular genetics of frontotemporal lobe dementia has become much more complex in recent years.

- Many cases now have been linked genetically to markers on chromosome band 17q21-22, the gene locus for the tau protein.

- The tau gene marker has linked cases of frontotemporal lobe dementia in several Dutch families, cases of hereditary dysphasic dementia reported in the United States, and a variety of other clinical syndromes called tauopathies, including familial parkinsonism with dementia, corticobasal degeneration, Pick disease without Pick bodies, and progressive supranuclear palsy. Overlap cases with these other tauopathies have been reported. The pathophysiology involves abnormal tau proteins, leading to the new terminology of frontotemporal lobe dementia as one of a series of tauopathies.

- In the words of an editorial by Wilhelmsen, the linkage of frontotemporal lobe dementia with this gene site has put frontotemporal lobe dementia "on the map" (ie, gene map).[15 ]Many cases of familial frontotemporal dementia with specific tau mutations have now been reported. On the other hand, apolipoprotein E4 (apoE4), which increases the risk for late-onset, sporadic AD, does not appear to have increased frequency in patients with frontotemporal lobe dementia or primary progressive aphasia.

- In the 2008 published series by Seelaar et al of 364 patients with frontotemporal dementia, 27% had positive family histories, which suggests autosomal dominant inheritance. Of these, 11% had tauopathies secondary to mutations of the MAPt gene on chromosome 17.[14 ]

- As mentioned above, the most patients with a frontotemporal lobe dementia syndrome have FTLD-U. Cases of frontotemporal lobe dementia and motor neuron disease usually have ubiquitin staining (sometimes called FTLD-MND). The FTLD-U group has itself been subdivided. In one classification scheme, FTLD-U type 1 is associated with semantic dementia, FTLD-U type 2 is associated with FTD-MND and bvFTD, and FTLD-U type 3 is associated with both bvFTD and progressive nonfluent aphasia. Some of these FTD-U variants are also inherited as autosomal dominant traits through the progranulin mutation, also found on chromosome 17. In the series by Seelaar et al, 6% had progranulin mutations.[14 ]

- Seelaar et al found that 10% had autosomal dominant inheritance patterns without a specific, demonstrated molecular genetic abnormality, adding up to 27% with autosomal dominantly inherited disorders. The other 73% of cases in their series were not clearly hereditary, and the molecular genetic basis of these disorders is not yet understood.[14 ]

- Formerly, patients with all of these pathologies were lumped together under the term dementia lacking specific histological features, or nonspecific dementia. Currently, most cases with autopsy study can be placed either in the tauopathy or the ubiquitin categories, so only rare cases are truly nonspecific.[5 ]

Differential Diagnoses

Pick Disease

Workup

LABORATORY STUDIES

- Routine testing (eg, blood, cerebrospinal fluid) in frontotemporal dementia is usually unrevealing.

- The genetic test for apoE4 is less useful in frontotemporal dementia than in Alzheimer disease. A study by Mesulam et al found no association between frontotemporal dementia and the apoE4 genotype.[16 ]Other studies have had somewhat different results, but, in general, apoE4 correlates much better with Alzheimer disease than with frontotemporal dementia.

Imaging Studies

- Routine brain

imaging with computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

is usually remarkable only for cerebral atrophy.

- Some patients show impressive localized atrophy in the frontal or temporal lobe on one or both sides.

- On MRI, temporal lobe atrophy is especially easy to detect in the coronal projections. Cases differ as to the relative degree of atrophy in the frontal or temporal lobe and on the left versus right side. Research studies using voxel-based morphometry have provided more precise maps of the areas of focal atrophy.

- Patients with frontal lobe neurobehavioral disorders (behavioral variant frontotemporal lobe dementia) often have bilateral frontal atrophy, especially involving the medial frontal cortex, sometimes with anterior temporal lobe atrophy as well.

- Whitwell et al reported in 2006 that cases associated with motor neuron disease have more paracentral atrophy by voxel-based morphometry on MRI.[12 ]

- Patients with progressive nonfluent aphasia tend to have perisylvian, left hemisphere atrophy, involving both the frontal and temporal lobes.

- Patients with semantic dementia typically have temporal lobe atrophy, sometimes bilaterally.

- Patients

with the related tauopathy progressive supranuclear palsy have midbrain

tegmentum and superior cerebellar peduncle atrophy, and those with corticobasal

degeneration have frontoparietal atrophy.

- Functional

imaging techniques, particularly single photon emission computed tomography

(SPECT) and positron emission tomography (PET), detect focal lobar hypometabolism

or hypoperfusion with great sensitivity.

- The Hammersmith PET facility in London published early studies by Tyrell et al, demonstrating that left temporal hypometabolism was observed in virtually all early cases of primary progressive aphasia.[17 ]

- More advanced

cases also showed hypometabolism in the left frontal lobe and, occasionally,

a lesser degree of hypometabolism in the right hemisphere.

- These patterns

of cortical involvement have been confirmed in many subsequent studies.

- The pattern

of frontal and/or temporal involvement is distinct from that of Alzheimer

disease, in which both parietal lobes tend to show the earliest hypometabolism.

- New ligands used to bind to amyloid protein deposits (eg, Pittsburgh Compound B) are helpful in the diagnosis of Alzheimer disease but not frontotemporal lobe dementia.

Other Tests

- Other than

brain imaging studies, the most specific tests for evaluating frontotemporal

dementia are evaluation with standardized language batteries and neuropsychological

testing.

- Such studies assess the specific pattern of language abnormality and the presence of other cognitive and memory deficits.

- Preservation

of many of these functions distinguishes frontotemporal dementia and

primary progressive aphasia syndromes from Alzheimer disease.

- The EEG findings are commonly abnormal in frontotemporal dementia, often showing focal slowing of electrical activity over one or both frontal or temporal lobes. These findings are not sufficiently specific to be clinically useful, and, in general, EEG is less useful than functional brain imaging with PET and even lobar atrophy on MRI.

Histologic Findings

Various pathologic findings have been reported in patients with primary progressive aphasia and frontotemporal lobe dementia. The central theme of these reports is that these syndromes have a non-Alzheimer pathology.

Considering first the cases of primary progressive aphasia, Pick disease was the first pathologic disease associated with this syndrome. This was reported with a description of the language syndrome in 1892. The neuropathological features of Pick disease are focal, lobar atrophy of the frontal and/or temporal lobes of one or both hemispheres, prominent gliosis associated with swollen neurons, and/or argentophilic inclusions (Pick bodies). In the current era, several groups have reported cases of pathologically proven Pick disease. Holland et al[18 ], Wechsler et al[19 ], and Graff-Radford et al[20 ]have reported patients with pathologically proven Pick disease and progressive language deterioration. All patients described in these reports had slowly progressive language symptoms, with naming involved early. In all cases, enough cognitive functions were spared initially to make the disorder easily distinguishable from typical Alzheimer disease.

Many reported cases do not have Pick bodies but have the less

specific findings of lobar atrophy, neuronal loss, gliosis, and microvacuolization.

These cases were previously referred to as dementia without specific histological

features, but this term was used before the newer histological stains

for tau and ubiquitin proteins entered routine use. This nonspecific pattern

of neuronal loss, gliosis, and microvacuolization was reported in 2 cases

as a pathologic underpinning of primary progressive aphasia.[21

]

Similar changes have also been reported by Morris et al[22

]under the term hereditary dysphasic dementia and by English authors

Neary, Snowden, and colleagues under the term frontal lobe dementia. As noted

in Causes, most non-Alzheimer disease pathologies can be divided into those

with positive staining for tau proteins, including those linked to chromosome

17, and those with ubiquitin staining (FTLD-U), leaving only rare cases with

truly nonspecific pathology.[23 ]Among the tau-positive

patients, some develop symptoms and show pathologic criteria for corticobasal

degeneration and others show overlap with the progressive supranuclear

palsy pathology. Cases with ubiquitin staining have been divided into 3 subtypes,

as discussed earlier, and these include both the motor neuron disease and

frontotemporal lobe dementia cases (FTLD-MND) and the patients with a progranulin

mutation on chromosome 17.

Alzheimer disease, the most common dementing illness, can mimic almost any

of the frontotemporal lobe dementia variants when it presents with focal

symptoms. Only a few cases of pathologically confirmed Alzheimer disease have

been reported that presented with isolated nonfluent aphasia, but more have

been described with the syndromes of semantic dementia (though other cases

of semantic dementia have the FTLD-U pathology) and with the logopenic variant

of primary progressive aphasia.

Kertesz et al have suggested the term Pick complex to include these various non-Alzheimer pathologies, with or without Pick inclusion bodies and with or without motor neuron disease.[24 ]

Treatment

MEDICAL CARE

To date, most efforts have concentrated on diagnosing frontotemporal

dementia and understanding its pathogenesis. Medical treatment is largely

nonexistent.

- Social interventions,

counseling, and speech/language/cognitive therapy to facilitate the use

of spared functions may make the condition easier to bear for the patient,

caregivers, and family members.

- Treatment

of depression with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), such

as sertraline or escitalopram, is frequently helpful. Trazodone may be helpful

for sleep. These agents have been shown effective in small clinical trials.

- Neurotransmitter-based

treatments, analogous to the use of dopaminergic agents in Parkinson disease

or anticholinesterase agents in Alzheimer disease, have not proven beneficial

in frontotemporal dementia. Anecdotal experience, including that of the

author, has not suggested a benefit similar to that of Alzheimer disease

with anticholinesterase agents or memantine, but clinical trials have not

been reported.

- All of the

pharmacologic treatments listed below must be considered investigational

and not recommended for general use.

- Anticholinesterase therapy generally involves donepezil (Aricept), rivastigmine (Exelon), and galantamine (Razadyne). As stated above, only occasional patients appear to respond. The same is true of attempted treatment with the drug memantine (Namenda), Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved in January 2004 for Alzheimer disease. This drug may improve the signal-to-noise ratio of glutamatergic transmission.

- Dopaminergic drugs have been tested in patients with transcortical motor aphasia secondary to strokes. Anecdotal experience with dopamine agonist agents such as bromocriptine (Parlodel), pergolide (Permax), pramipexole (Mirapex), and ropinirole (Requip) has been unimpressive.

- Stimulant drugs such as amphetamines and antidepressant agents may benefit patients with frontal lobe syndromes. Large, randomized, double-blind studies are lacking, but a few small trials are cited in the references.

Medication

All current pharmacologic treatments are unproven, but SSRI antidepressants and trazodone are widely recommended. As discussed above, the cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine have not been shown to be effective in primary progressive aphasia or frontotemporal dementia (see Treatment).

Follow-up

PATIENT EDUCATION

For excellent patient education resources, visit eMedicine's Dementia Center. Also, see eMedicine's patient education articles Dementia Overview and Dementia Medication Overview.

Multimedia

Media file 1: Patient with progressive nonfluent aphasia. MRI showing focal, left temporal atrophy. Reprinted from Neurology in Clinical Practice, 4th ed. Kirshner H. Language and Speech Disorders. Copyright 2004, with permission from Elsevier.

Media file 2: Patient with progressive nonfluent aphasia. Positron emission tomography (PET) scan indicating hypometabolism of glucose in the left hemisphere. Reprinted from Neurology in Clinical Practice, 4th ed. Kirshner H. Language and Speech Disorders. Copyright 2004, with permission from Elsevier.

Media file 3: Hematoxylin and eosin stain of the left frontal cortex from a patient with primary progressive aphasia. This shows loss of neurons, plump astrocytes (arrow), and microvacuolation of the superficial cortical layers. Reproduced with permission of John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Media file 3: Hematoxylin and eosin stain of the left frontal cortex from a patient with primary progressive aphasia. This shows loss of neurons, plump astrocytes (arrow), and microvacuolation of the superficial cortical layers. Reproduced with permission of John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

REFERENCES

-

Pick A. On the relationship between aphasia and senile atrophy of the brain. In: Rottenbergb DA, Hochberg FH, eds. Neurological Classics in Modern Translation. 39(5). Hafner Press; 1977.

-

Mesulam MM. Slowly progressive aphasia without generalized dementia. Ann Neurol. Jun 1982;11(6):592-8. [Medline].

-

Kirshner HS, Webb WG, Kelly MP, et al. Language disturbance. An initial symptom of cortical degenerations and dementia. Arch Neurol. May 1984;41(5):491-6. [Medline].

-

Neary D, Snowden J. Fronto-temporal dementia: nosology, neuropsychology, and neuropathology. Brain Cogn. Jul 1996;31(2):176-87. [Medline].

-

Josephs KA. Frontotemporal dementia and related disorders: deciphering the enigma. Ann Neurol. Jul 2008;64(1):4-14. [Medline].

-

Boxer AL, Miller BL. Clinical features of frontotemporal dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. Oct-Dec 2005;19 Suppl 1:S3-6. [Medline].

-

Stevens M, van Duijn CM, Kamphorst W, et al. Familial aggregation in frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. Jun 1998;50(6):1541-5. [Medline].

-

Westbury C, Bub D. Primary progressive aphasia: a review of 112 cases. Brain Lang. Dec 1997;60(3):381-406. [Medline].

-

Miller BL, Hou CE. Portraits of artists: emergence of visual creativity in dementia. Arch Neurol. Jun 2004;61(6):842-4. [Medline].

-

Gorno-Tempini ML, Dronkers NF, Rankin KP, et al. Cognition and anatomy in three variants of primary progressive aphasia. Ann Neurol. Mar 2004;55(3):335-46. [Medline].

-

Hodges JR, Patterson K, Oxbury S, et al. Semantic dementia. Progressive fluent aphasia with temporal lobe atrophy. Brain. Dec 1992;115 (Pt 6):1783-806. [Medline].

-

Whitwell JL, Jack CR Jr, Senjem ML, et al. Patterns of atrophy in pathologically confirmed FTLD with and without motor neuron degeneration. Neurology. Jan 10 2006;66(1):102-4. [Medline].

-

Grossman M, Mickanin J, Onishi K. Progressive nonfluent aphasia: language, cognitive, and PET measures contrasted with probable Alzheimer's disease. J Cogn Neurosci. 1996;8:135-54.

-

Seelaar H, Kamphorst W, Rosso SM, et al. Distinct genetic forms of frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. Oct 14 2008;71(16):1220-6. [Medline].

-

Wilhelmsen KC. Frontotemporal dementia is on the MAPtau. Ann Neurol. Feb 1997;41(2):139-40. [Medline].

-

Mesulam MM, Johnson N, Grujic Z, et al. Apolipoprotein E genotypes in primary progressive aphasia. Neurology. Jul 1997;49(1):51-5. [Medline].

-

Tyrrell PJ, Warrington EK, Frackowiak RS, et al. Heterogeneity in progressive aphasia due to focal cortical atrophy. A clinical and PET study. Brain. Oct 1990;113 (Pt 5):1321-36. [Medline].

-

Holland AL, McBurney DH, Moossy J, et al. The dissolution of language in Pick's disease with neurofibrillary tangles: a case study. Brain Lang. Jan 1985;24(1):36-58. [Medline].

-

Wechsler AF, Verity MA, Rosenschein S, et al. Pick's disease. A clinical, computed tomographic, and histologic study with golgi impregnation observations. Arch Neurol. May 1982;39(5):287-90. [Medline].

-

Graff-Radford NR, Damasio AR, Hyman BT, et al. Progressive aphasia in a patient with Pick's disease: a neuropsychological, radiologic, and anatomic study. Neurology. Apr 1990;40(4):620-6. [Medline].

-

Kirshner HS, Tanridag O, Thurman L, et al. Progressive aphasia without dementia: two cases with focal spongiform degeneration. Ann Neurol. Oct 1987;22(4):527-32. [Medline].

-

Morris JC, Cole M, Banker BQ, et al. Hereditary dysphasic dementia and the Pick-Alzheimer spectrum. Ann Neurol. Oct 1984;16(4):455-66. [Medline].

-

Josephs KA, Whitwell JL, Duffy JR, et al. Progressive aphasia secondary to Alzheimer disease vs FTLD pathology. Neurology. Jan 1 2008;70(1):25-34. [Medline].

-

Kertesz A, Munoz DG. Primary progressive aphasia and Pick complex. J Neurol Sci. Jan 15 2003;206(1):97-107. [Medline].

-

Abe K, Ukita H, Yanagihara T. Imaging in primary progressive aphasia. Neuroradiology. Aug 1997;39(8):556-9. [Medline].

-

Alladi S, Xuereb J, Bak T, et al. Focal cortical presentations of Alzheimer's disease. Brain. Oct 2007;130:2636-45. [Medline].

-

Baker M, Mackenzie IR, Pickering-Brown SM, et al. Mutations in progranulin cause tau-negative frontotemporal dementia linked to chromosome 17. Nature. Aug 24 2006;442(7105):916-9. [Medline].

-

Bird TD. Genotypes, phenotypes, and frontotemporal dementia: take your pick. Neurology. Jun 1998;50(6):1526-7. [Medline].

-

Black SE. Focal cortical atrophy syndromes. Brain Cogn. Jul 1996;31(2):188-229. [Medline].

-

Clinical and neuropathological criteria for frontotemporal dementia. The Lund and Manchester Groups. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. Apr 1994;57(4):416-8. [Medline].

-

Davies RR, Hodges JR, Kril JJ, et al. The pathological basis of semantic dementia. Brain. Sep 2005;128:1984-95. [Medline].

-

Diehl J, Grimmer T, Drzezga A, et al. Cerebral metabolic patterns at early stages of frontotemporal dementia and semantic dementia. A PET study. Neurobiol Aging. Sep 2004;25(8):1051-6. [Medline].

-

Edwards-Lee T, Miller BL, Benson DF, et al. The temporal variant of frontotemporal dementia. Brain. Jun 1997;120 (Pt 6):1027-40. [Medline].

-

Forman MS, Farmer J, Johnson JK, et al. Frontotemporal dementia: clinicopathological correlations. Ann Neurol. Jun 2006;59(6):952-62. [Medline].

-

Forman MS, Mackenzie IR, Cairns NJ, et al. Novel ubiquitin neuropathology in frontotemporal dementia with valosin-containing protein gene mutations. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. Jun 2006;65(6):571-81. [Medline].

-

Geschwind D, Karrim J, Nelson SF, et al. The apolipoprotein E epsilon4 allele is not a significant risk factor for frontotemporal dementia. Ann Neurol. Jul 1998;44(1):134-8. [Medline].

-

Gorno-Tempini ML, Brambati SM, Ginex V, et al. The logopenic/phonological variant of primary progressive aphasia. Neurology. Oct 14 2008;71(16):1227-34. [Medline].

-

Graham NL, Bak T, Patterson K, et al. Language function and dysfunction in corticobasal degeneration. Neurology. Aug 26 2003;61(4):493-9. [Medline].

-

Green J, Morris JC, Sandson J, et al. Progressive aphasia: a precursor of global dementia?. Neurology. Mar 1990;40(3 Pt 1):423-9. [Medline].

-

Gustafson L, Abrahamson M, Grubb A, et al. Apolipoprotein-E genotyping in Alzheimer's disease and frontotemporal dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. Jul-Aug 1997;8(4):240-3. [Medline].

-

Heutink P, Stevens M, Rizzu P, et al. Hereditary frontotemporal dementia is linked to chromosome 17q21-q22: a genetic and clinicopathological study of three Dutch families. Ann Neurol. Feb 1997;41(2):150-9. [Medline].

-

Hodges JR, Davies RR, Xuereb JH, et al. Clinicopathological correlates in frontotemporal dementia. Ann Neurol. Sep 2004;56(3):399-406. [Medline].

-

Huey ED, Putnam KT, Grafman J. A systematic review of neurotransmitter deficits and treatments in frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. Jan 10 2006;66(1):17-22. [Medline].

-

Josephs KA, Holton JL, Rossor MN, et al. Neurofilament inclusion body disease: a new proteinopathy?. Brain. Oct 2003;126:2291-303. [Medline].

-

Josephs KA, Petersen RC, Knopman DS, et al. Clinicopathologic analysis of frontotemporal and corticobasal degenerations and PSP. Neurology. Jan 10 2006;66(1):41-8. [Medline].

-

Kersaitis C, Halliday GM, Xuereb JH, et al. Ubiquitin-positive inclusions and progression of pathology in frontotemporal dementia and motor neurone disease identifies a group with mainly early pathology. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. Feb 2006;32(1):83-91. [Medline].

-

Kertesz A. Frontotemporal dementia/Pick's disease. Arch Neurol. Jun 2004;61(6):969-71. [Medline].

-

Kertesz A, Hudson L, Mackenzie IR, et al. The pathology and nosology of primary progressive aphasia. Neurology. Nov 1994;44(11):2065-72. [Medline].

-

Kertesz A, Martinez-Lage P, Davidson W, et al. The corticobasal degeneration syndrome overlaps progressive aphasia and frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. Nov 14 2000;55(9):1368-75. [Medline].

-

Kertesz A, McMonagle P, Blair M, et al. The evolution and pathology of frontotemporal dementia. Brain. Sep 2005;128:1996-2005. [Medline].

-

Lebert F, Stekke W, Hasenbroekx C, et al. Frontotemporal dementia: a randomised, controlled trial with trazodone. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2004;17(4):355-9. [Medline].

-

Lippa CF, Cohen R, Smith TW, et al. Primary progressive aphasia with focal neuronal achromasia. Neurology. Jun 1991;41(6):882-6. [Medline].

-

Mesulam MM. Primary progressive aphasia--a language-based dementia. N Engl J Med. Oct 16 2003;349(16):1535-42. [Medline].

-

Mesulam MM. Primary progressive aphasia. Ann Neurol. Apr 2001;49(4):425-32. [Medline].

-

Moretti R, Torre P, Antonello RM, et al. Frontotemporal dementia: paroxetine as a possible treatment of behavior symptoms. A randomized, controlled, open 14-month study. Eur Neurol. 2003;49(1):13-9. [Medline].

-

Mott RT, Dickson DW, Trojanowski JQ, et al. Neuropathologic, biochemical, and molecular characterization of the frontotemporal dementias. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. May 2005;64(5):420-8. [Medline].

-

Neary D, Snowden JS, Gustafson L, et al. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: a consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria. Neurology. Dec 1998;51(6):1546-54. [Medline].

-

Neary D, Snowden JS, Mann DM, et al. Frontal lobe dementia and motor neuron disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. Jan 1990;53(1):23-32. [Medline].

-

Sakurai Y, Hashida H, Uesugi H, et al. A clinical profile of corticobasal degeneration presenting as primary progressive aphasia. Eur Neurol. 1996;36(3):134-7. [Medline].

-

Seeley WW, Bauer AM, Miller BL, et al. The natural history of temporal variant frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. Apr 26 2005;64(8):1384-90. [Medline].

-

Snowden J, Neary D, Mann D. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: clinical and pathological relationships. Acta Neuropathol. Jul 2007;114(1):31-8. [Medline].

-

Sonty SP, Mesulam MM, Thompson CK, et al. Primary progressive aphasia: PPA and the language network. Ann Neurol. Jan 2003;53(1):35-49. [Medline].

-

Weintraub S, Rubin NP, Mesulam MM. Primary progressive aphasia. Longitudinal course, neuropsychological profile, and language features. Arch Neurol. Dec 1990;47(12):1329-35. [Medline].

Keywords

frontotemporal dementia, frontal dementia, semantic dementia, nonspecific dementia, Pick's disease, Pick disease, primary progressive aphasia, FTD, PPA, tauopathy, motor neuron disease, Alzheimer disease, Alzheimer's disease, AD, fluent aphasia, nonfluent aphasia

Contributor Information and Disclosures

Author

Howard

S Kirshner, MD, Professor of Neurology, Psychiatry and Hearing

and Speech Sciences, Vice Chairman, Department of Neurology, Vanderbilt University

School of Medicine; Director, Vanderbilt Stroke Center; Program Director,

Stroke Service, Vanderbilt Stallworth Rehabilitation Hospital; Consulting

Staff, Department of Neurology, Nashville Veterans Affairs Medical Center

Howard S Kirshner, MD is a member of the following medical societies: Alpha

Omega Alpha, American Academy of Neurology, American Heart Association, American

Medical Association, American Neurological Association, American Society of

Neurorehabilitation, National Stroke Association, Phi Beta Kappa, and Tennessee

Medical Association

Disclosure: BMS/Sanofi Honoraria Speaking and teaching

Medical Editor

Robert

A Hauser, MD, MBA, Professor of Neurology, Molecular Pharmacology

and Physiology, Director, Parkinson's Disease and Movement Disorders Center,

University of South Florida; Clinical Chair, Signature Interdisciplinary Program

in Neuroscience

Robert A Hauser, MD, MBA is a member of the following medical societies: American

Academy of Neurology, American Medical Association, American Society of Neuroimaging,

and Movement Disorders Society

Disclosure: Allergan Sales, LLC Honoraria Speaking and teaching; Boehringer

Ingelheim Honoraria Consulting; Genzyme Corporation Honoraria Consulting; GlaxoSmithKline Honoraria Consulting; IMPAX

Laboratories, Inc. Honoraria Consulting; Novartis Pharmaceuticals

Corp. Honoraria Consulting; Schering Plough Consulting; Solvay

Pharmeceuticals Honoraria Consulting; Teva Neuroscience Honoraria Speaking

and teaching

Pharmacy Editor

Francisco

Talavera, PharmD, PhD, Senior Pharmacy Editor, eMedicine

Disclosure: eMedicine Salary Employment

Managing Editor

Richard

J Caselli, MD, Professor, Department of Neurology, Mayo Medical

School, Rochester, MN; Chair, Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic of Scottsdale

Richard J Caselli, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American

Academy of Neurology, American Association of Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic

Medicine, American Medical Association, American Neurological Association,

and Sigma Xi

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Chief Editor

Howard

A Crystal, MD, Professor, Departments of Neurology and Pathology,

State University of New York Downstate; Consulting Staff, Department of Neurology,

University Hospital and Kings County Hospital Center

Howard A Crystal, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American

Academy of Neurology and American Neurological Association

Disclosure: Medivations Honoraria Consulting